As Satellite Launches Soar, Spotlight Turns to Stations Back on Earth

A proliferation of satellites in space is sparking a wave of investment on Earth. A proposed deal with Eutelsat aims to create the largest independent ground station operator.

- The nature and scale of the space economy are changing with the rapid growth of satellites in low-Earth orbit.

The number of satellite launches is soaring, but the action is not confined to the sky. Back on Earth, companies and investors are turning their attention to the ground stations that play a vital role in sending vast amounts of data around the world.

Advances in technology have made satellites smaller, more powerful and less expensive to deploy, fueling a surge in their numbers to meet the growing demand for the connectivity and imaging services they provide. The sector is attracting increasing investment from giant companies like SpaceX’s Starlink and Amazon, as well as large-scale public funds from the U.S., UK, Canada and the European Union.

More satellites in space require more infrastructure on Earth to send and receive signals. Those ground stations – sites housing antennas and other equipment – are the crucial gateway between satellites in orbit and the vast networks of cable on Earth. Satellite companies typically own and run their own ground operations, but as more data gets beamed down, they are exploring whether that infrastructure would be better off in the hands of other companies, which could build scale and drive efficiencies.

“Space assets are projected to grow for the next 10 years,” Bill Farmer, a managing director and aerospace and defense specialist at Brown Gibbons Lang & Company, a U.S.-based investment bank and advisory firm, said in an interview. “You’ll need this ground infrastructure to handle that. It’s a huge market opportunity.”

Busy skies

The demands placed on ground stations are evolving.

The sky was once dominated by so-called GEO satellites orbiting at an altitude of around 22,200 miles, which track the rotation of the Earth. The majority of new launches are destined for the nearest part of space, known as Low-Earth Orbit, or LEO, which spans altitudes between 100 and 1,200 miles. The number of LEO satellites, which offer lower launch costs and faster communication, is forecast to increase rapidly, growing to a multiple of the roughly 7,000 orbiting today. According to analysts at Goldman Sachs, as many as 70,000 could be sent into space over the next five years.

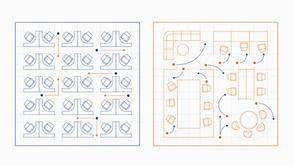

While GEO satellites appear stationary from the ground, LEO satellites move rapidly across the sky, circling the Earth every 90 minutes or so, and they are visible from only a small part of the Earth’s surface at any one time. As a result, both the number of satellites in a LEO constellation and the number of ground stations need to be far greater than for those in higher orbits to provide broad coverage. An Earth-based antenna for a GEO satellite points permanently in one direction, but those communicating with LEO constellations need to track satellites across the sky, and hand over to antennas at different locations when a particular satellite moves out of their field of vision.

First of its kind

Satellite technology has the potential to close the digital divide, providing connectivity to even the remotest locations, and a boom in launches reflects the increasing need for reliable internet access in areas where cable cannot reach.

With data demand rising exponentially, satellite operators are exploring how they can achieve their growth ambitions in the most efficient way, expanding in space while ensuring that investment continues to flow into key infrastructure on Earth. French satellite operator Eutelsat has agreed to sell 80 percent of its ground station business to EQT, carving out 1,400 antennas and other infrastructure into a standalone business. The proposed transaction with Eutelsat, whose satellites are also used to connect planes, trains and ships, is seen as the first of its kind in the industry.

“People get excited about space and getting satellites launched into orbit,” said William Lindström, a managing director at EQT based in Stockholm. “What we want to do is help them with the stuff that’s a hassle to deal with on the ground: permits, local regulations, construction. We have a perfect network to do so.”

Similar deals are likely to follow as ground infrastructure assets attract more investors seeking stable, long-term cash flows.

Market projections for low-Earth orbit satellites

Enabling different operators to share space on the ground for their antennas lowers costs and reduces the amount of land needed to build these sites. Marc-Alexander Straubinger, also a managing director for EQT, described the proposed business as “a one-stop shop” that will help meet satellite operators’ global ground coverage needs.

Supply magnet

Dedicated ground station businesses could also encourage start-ups to jump into the sector, said Luke Wyles, an analyst at consulting firm Analysys Mason. “Having antenna space that is ready to be occupied is a supply magnet for players to get in the space without having to face the capex of deploying their own systems,” he said.

As the sector heats up, both companies and investors see an opportunity to help strengthen the industry and capitalize on rapid growth in demand. The size of the ground station market is projected to more than triple by 2032.

“Being a global provider of scale, we can up the game when it comes to security, cyber management and operating a resilient network compared to what has been in the market in this field historically,” EQT’s Lindström said.

ThinQ by EQT: A publication where private markets meet open minds. Join the conversation – [email protected]