Can Scientific Breakthroughs Unblock Critical Mineral Supply Chains?

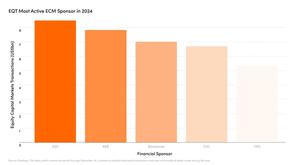

As the transition to clean energy accelerates, a critical mineral shortfall looms. The EQT Foundation is launching a grant program to find innovative alternatives.

- Renewable energy output surpassed coal in 2025, but the supply of critical minerals such as lithium is struggling to keep up with demand.

As the global energy transition away from fossil fuels continues apace, the availability of materials such as cobalt and nickel is getting squeezed. A new science grant from the EQT Foundation, EQT’s charitable arm, aims to find alternatives to these critical minerals, which are key components of batteries and other electricity infrastructure.

Energy produced by renewables surpassed coal for the first time in the first half of 2025, with capacity growing at a record rate, driven by solar and wind. However, efforts to meet global clean energy targets are facing a looming threat. The supply of critical minerals from existing and announced projects for mining and refinement falls far short of projected demand, according to estimates from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

“Assuming renewable generation capacity is built out in line with the IEA’s Net Zero Emissions by 2050 scenario, several critical minerals — including copper and lithium — are expected to face supply deficits during the 2030s,” says Parham Abuhamzeh, a managing director in EQT’s Infrastructure team. “Without substantial investment in new mining capacity, supply will be insufficient to meet projected demand.”

Production of such minerals is also concentrated in a few locations, introducing geopolitical risks. China is the top refiner of 19 of 20 key minerals, with an average market share of 70 percent, according to the IEA. About half the world’s nickel, a metal essential to electric vehicle production, comes from just one country: Indonesia.

“It's not a matter of whether there are enough reserves or resources in the world, but can we produce them at acceptable speed,” says Moana Simas, a specialist in critical mineral supply chains and researcher for the SINTEF research foundation.

Growing clean energy investment

While clean energy investment reached $2tn in 2024, double the amount of 2020, it falls far short of the $5.6tn needed annually through 2030, according to estimates from BloombergNEF. Batteries will play an important role, but they require large amounts of graphite, copper, lithium and nickel. A wind farm delivering the same power as a gas turbine may need more than six times the amount of minerals, according to Abuhamzeh.

Simas explains that the limits on production hang in the maturity of critical mineral supply chains. The use of metals like copper and aluminum in production has been established for some time, meaning the infrastructure, logistics and knowledge around these materials have had time to develop along with demand.

For critical materials, demand has spiked over the last few decades, leaving the industries around them little time to catch up. Nickel, for example, had been used for some time in the production of stainless steel. However, the extra demand caused by the rising need for batteries and other clean technology infrastructure has pushed suppliers to their limits. Nickel production is projected to plateau by 2030, only just fulfilling the projected increase in demand, she says.

“It can take 10 years to open a mine from when you discover the resource until you start to operate it commercially,” says Simas. With some governments committing to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions within 24 years, it doesn’t leave a lot of time.

There are also environmental and geopolitical costs to relying heavily on new mining, just as societies attempt to cut emissions. Mineral extraction is highly energy‑intensive and often water‑intensive, generating significant local impacts from land disturbance and pollution. “Mining is a resource-intensive activity with meaningful negative environmental effects,” notes Abuhamzeh.

Future solutions

The current threats to supply are pushing governments and industry to find near- and long-term solutions that reduce clean technologies’ dependency on critical minerals.

Improving recycling infrastructure, Simas explains, is one way short-term supply can be boosted. At present, legacy metals such as aluminum have relatively well‑established recycling loops, but even those will need to “scale massively” to meet future demand.

For newer equipment categories like EV batteries and permanent magnets, value chains and practices are much less developed, driving a need for research. “Without effective recycling, reliance on newly mined minerals will remain,” says Abuhamzeh. According to the IEA, the growth needed to meet demand for critical minerals could be brought down by between 25-40 percent by 2050 by scaling up recycling. “We need to build new recycling value chains,” he continues.

In a recent report around the recycling of critical materials, the IEA pointed to mining waste as an important potential source of minerals. However, current research and existing technologies are not sufficient for the useful minerals to be extracted effectively, driving a need for further research and development (R&D).

Longer-term innovation efforts have focused on reducing the reliance on critical minerals by producing alternative products. Tesla, for instance, announced at its 2023 Investor Day that its next‑generation vehicle would use a permanent‑magnet motor designed with zero rare earth elements.

“It’s solving the problem by applying constraints,” says Simas. “The challenge is to maintain the same efficiency and the same characteristics.”

Researchers are also approaching the chemistry of components like batteries, in attempts to reduce or eliminate a dependency on critical minerals like lithium. Sodium, for example, is an abundant material that is easy to extract, providing an attractive alternative to lithium. Sodium batteries, initially overlooked due to lower capacity, are now showing commercial promise as lithium alternatives through continued experimentation.

Investment as a catalyst

Funding is a significant driver of these breakthroughs. “Thanks to targeted investments and R&D efforts, demand-side innovations have made tremendous progress in recent years,” reads the IEA Critical Minerals Outlook Report 2025.

Despite the success of targeted investment, there is a need for a significant increase in funding and development to meet green transition targets. The required investment for mineral production alone to meet climate targets is projected to be above $590bn. In 2023, G7 countries collectively committed only $13bn.

On January 27th, the EQT Foundation launched a new grant program focused on innovation in the critical minerals sector. Targeted at both finding new ways of enhancing supply capabilities and reducing critical mineral reliance, they aim to push research at both sides of the problem.

“There's a level of technical innovation necessary to unlock this potential,” says Abuhamzeh. With initiatives like the EQT Foundation's grants targeting both supply enhancements and mineral reduction technologies, research in the sector continues to evolve in response to material supply challenges.

ThinQ by EQT: A publication where private markets meet open minds. Join the conversation – [email protected]

MoreInsights

Exclusive News and Insights Every Week

Sign up to subscribe to the EQT newsletter.