The Breakthrough Era for Cancer Vaccines

A new generation of vaccines in development could be “the difference between the cancer coming back and not coming back,” according to EQT Partner Joachim Rothe.

- Vaccines represent one of the future frontiers of cancer treatment.

In the final weeks of 2023, two U.S. pharmaceutical firms achieved the biggest breakthrough so far in the long quest for a cancer vaccine. Moderna and Merck jointly developed a personalized vaccine for melanoma, a type of skin cancer, which showed promising results in its phase two trials. Three years after cancer patients had been vaccinated, the risk of recurrence or death had fallen by nearly half.

Known as mRNA-4157, the drug was used to treat patients who had skin cancer tumors removed. As it moves into phase three trials for final proof of its usefulness, the results are encouraging for the drug itself and, more broadly, the entire cancer vaccine industry.

With cancer responsible for nearly one in six deaths, according to the World Health Organization, widely available vaccines would prove a game changer for patients’ longevity. By the end of the decade, it appears possible that vaccines will exist for several major types of cancer, making the prognosis for the growing number of people with the disease far more promising.

The progress of mRNA-4157 has opened the door for further vaccine development. “Moderna and Merck’s success with this vaccine has given a tailwind to the whole cancer vaccine industry because, for the first time, it has provided evidence that the approach can work,” explains Joachim Rothe, a Partner in the EQT Life Sciences team.

Cancer vaccines in development

Quietly, a surprisingly large number of vaccines are in development. In 2023, there were approximately 500 preclinical and discovery-stage vaccines, according to the U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information database. About 130 were in phase one trials, 130 in phase two and 22 in phase three – although many may be run by universities without sophisticated controls or deep pockets.

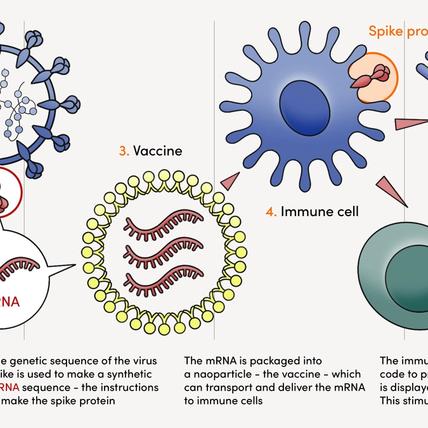

Most of these fledgling vaccines aim to mop up remaining malignant cancer cells after surgery or chemotherapy to prevent reoccurrence, although a few are preventative. Many are personalized vaccines, tailored to an individual’s malignant tumor. Melanoma is a popular target, as tumors can easily be removed for biopsies, after which mRNA technology or other vector technologies tailor a vaccine. However, some are off-the-shelf vaccines that oncologists can prescribe to anyone suffering from a specific type of cancer.

Cancer cells contain hundreds, if not thousands, of mutations that distinguish them from healthy cells. Some of these mutations cause cancer cells to produce abnormal proteins, known as neoantigens, that set alarm bells ringing in the body’s immune system. The idea of a vaccine is to introduce these neoantigens into the body, priming the immune system to see any cancer cell that carries them as a target for elimination.

“Cancer vaccines have a very important role to play because their job is to identify the bad guys, the cancer cells, wherever they’re hiding, and attract the immune system and get them destroyed,” noted Rothe. “On the individual level, it could make a very large difference. In many cases, hopefully, the difference between the cancer coming back and not coming back.”

The anti-cancer toolkit

Nouscom, a Swiss immunotherapy company based in Basel and backed by EQT, has some of the most promising vaccines. Unlike Moderna and Merck, though, its vaccines are delivered by an adenovirus rather than mRNA. This method of delivery, or vector platform, is known to generate the kind of strong and long-term responses from neoplastic cells that will be needed for cancer vaccines to join the anti-cancer toolbox.

Since EQT invested in 2015, Nouscom has been working on three vaccines. Notably, it’s developing the NOUS-209 vaccine not only for a form of colon cancer but also for Lynch Syndrome, a genetic disorder linked to colorectal cancer. Nouscom starts phase two trials for this vaccine later in 2025. The company is also developing an off-the-shelf vaccine for colon and gastric cancer, with phase two data expected in spring 2025. Thirdly, it is developing a personalized vaccine for melanoma.

As the number of successful clinical trials grows, so the technology matures. Confidence is mounting, encouraging further investments that stretch into hundreds of millions of dollars for individual vaccines. Much could still go wrong in trials to come, but it seems possible that, by the end of the decade, some vaccines may be approved by the agencies authorizing drugs.

When and if that happens, it will make a huge difference to individual patients, even if cancer remains one of the biggest killers globally.

“Cancer vaccines will no longer be a fantasy,” explains Vincent Brichard, a Venture Partner in the EQT Life Sciences team with more than 25 years’ experience in oncology and immunology. “Twenty years ago, pharma companies did not dare invest in cancer vaccines. They said it might work on mice but wouldn’t on humans. But now I think we’re close to reality.”

ThinQ by EQT: A publication where private markets meet open minds. Join the conversation – [email protected]