Why Is The Stock Market Shrinking?

Public companies have shrunk rapidly in the past two decades. What’s happening, and what does it mean for the future of the stock market?

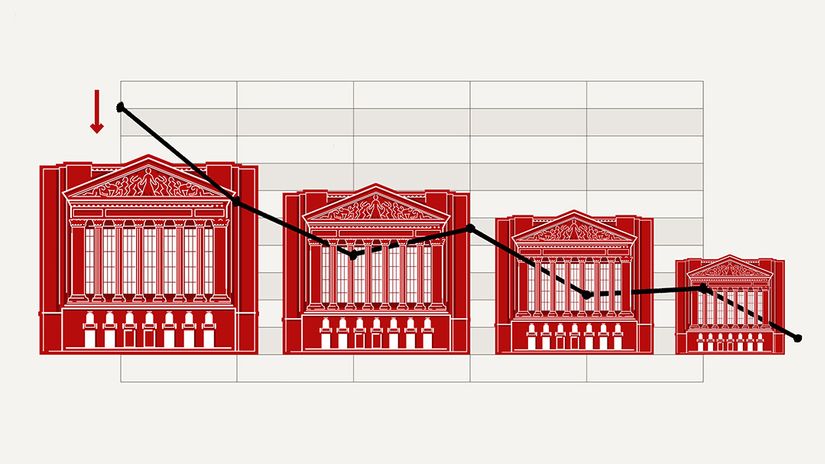

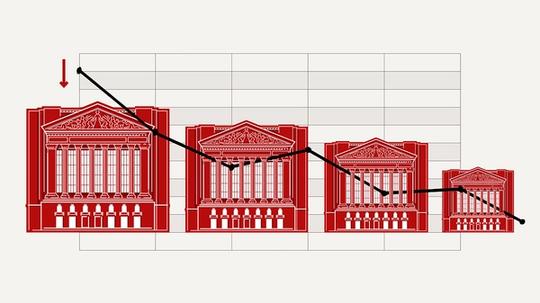

- The number of publicly traded companies in the U.S. peaked at 7,300 in 1996; it's now down to 4,300.

Here’s a puzzling figure: America’s stock market has shed nearly half its companies in the last two decades. The number of publicly traded U.S. companies fell from a peak of 7,300 in 1996 to 4,300 today.

“That total should have grown dramatically, not shrunk,” said JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon in an April letter to shareholders. The trend is evident in other public equity markets, too: The number of global public companies grew throughout the 1980s and 1990s, leveled off around 2000, and started to decline around 2014. So what’s going on?

Being listed is a complicated business

Part of the story is a sharp downward trend in the number of Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), particularly among small firms. Between 1980 and 2000, an average of more than 300 companies a year went public in the United States; since then, the figure is less than 100.

Many, including Dimon, have suggested that companies are being deterred from joining the public markets by the increasing complications associated with being listed. Faced with ever-increasing reporting requirements, the relentless pressure and short-termism of quarterly earnings reports, and intense scrutiny from investors, companies may be deciding that going public just isn’t worth the hassle.

To take just one example, annual reports have lengthened by 46 percent in just 5 years, according to research. The average FTSE 100 annual report is now 147,000 words long and growing by 8,400 words a year. Being a public company is also eye-wateringly expensive: The median U.S. company spends 4.1 percent of its market capitalization every year on compliance by one estimate. Regulatory demands and reporting requirements continue to intensify, and that burden is only set to increase.

Why companies are staying private

Perhaps more significantly, private capital is more widely available and easier for companies to access than ever.

In the same period that the U.S. shed half its public companies, the number backed by private equity firms increased from 1,900 to 11,200, according to JPMorgan.

Bain & Co., a consulting firm, expects private market assets under management to grow more than twice the rate of public assets to reach up to $65 trillion by 2032. That growing pool of capital means that companies today can raise tens of billions of dollars from private markets without going public.

Companies see plenty of advantages to remaining private for longer — or indeed indefinitely. For one thing, it offers companies the ability to focus on long-term growth without the perceived short-termism associated with quarterly earnings calls and shareholder pressure.

Good private investors can also provide deep sectoral knowledge. Before Microsoft floated in 1986, the only capital the firm had raised was from venture capital investor and engineer Dave Marquardt, who CEO Bill Gates brought in for his expertise rather than the capital he provided. “That money sat in the bank, and it's still in the bank today, so it was not for anything to do with capital, but rather just [for him] to join the team,” Gates said.

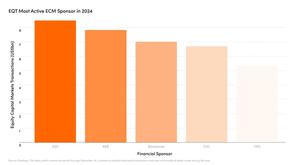

To be sure, private equity investors also list companies on the stock markets as well as backing them while they grow. EQT-owned companies were involved in equity capital market (ECM) deals worth a combined $8.6bn in 2024, the largest cohort globally by total volume of deals of any private equity manager portfolio, according to data compiled by Dealogic and Goldman Sachs. (ECM deals refer to selling shares in an IPO or secondary sales to investors.)

A magnificently concentrated stock market

Whether or not the trend of shrinking public companies is a positive development for retail investors is partly a question of perspective. Some academics have pointed to the fact that companies are entering the public market once they’re out of their growth phase, meaning savers could face lower but more predictable returns on those investments.

Fewer public companies also means a higher likelihood of greater market concentration, which could have downside risks for investors. The “Magnificent Seven” tech stocks — Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, NVIDIA and Tesla — alone represent around a third of the S&P 500’s total market capitalization. Meanwhile, the share of money being passively invested in public markets has sky-rocketed — from less than 2 percent in 1995 to more than 50 percent today. That market concentration, combined with the dominance of passive investing, could point to significantly more market volatility in the event of a downturn.

In the meantime, the stock market has come to represent a shrinking share of the corporate world. Schroders notes that fewer than 15 percent of U.S. companies with revenue over $100m are publicly listed. Ordinary savers are largely unable to invest in the rest. That is starting to change: 16 percent of retail assets under management were allocated to private market assets in 2022, according to Bain, which expects that figure to increase to 22 percent by 2032. In the meantime, the question of whether or not the stock market will rediscover its appeal for companies remains to be seen.

ThinQ by EQT: A publication where private markets meet open minds. Join the conversation – [email protected]

On the topic ofPrivate Markets

Exclusive News and Insights Every Week

Sign up to subscribe to the EQT newsletter.